I was 14-years-old, sitting in my freshman geometry class, when I saw three boys throwing paper wads at a mentally challenged student named Angel*. I sat in my seat from across the room, staring at the boys continuing to haze Angel. I felt disgust for this act and wanted to catch each paper wad before it hit Angel, but my body was frozen and did not know what to say —or how to say it.

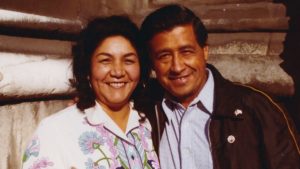

This Women’s History Month, we can learn the importance of speaking up for others from Helen Fabela Chávez. Chávez was the wife of American civil rights activist Cesar Chávez, although he was heralded as a Latin American hero, not many people know Helen, an activist, had a critical role in establishing the National Farm Workers Association, later changed to United Farm Workers (UFW). The UFW would establish humane working conditions for the nation’s farmworkers, many who at the time were American citizens of Mexican descent or Mexican immigrants, according to the Los Angeles Times.

“Her consistent humility, selflessness, quiet heroism and fiery perseverance were at the heart of the movement she helped build,” the UFW said in a statement responding to Chávez’s death in 2016. “Her actions changed the lives of thousands of farmworkers and millions of others who were inspired by La Causa (the cause).”

According to Psychology Today, women often feel torn between speaking up and staying silent. In today’s society, women are taught to be more reserved and fear speaking out at the risk of hurting others feelings and told assertiveness isn’t graceful or feminine. Since 1848, women have been fighting for the same rights as men and still, in 2020, women earn 81 cents for every dollar a man makes.

There is a stereotype for Latinas who speak out and they are not known as affirmative or a leader like their male counterparts, but known as a “loud Latina.” This is something we have all experienced, especially in the workforce and can happen in any field of expertise. Latinas are passionate, affirmative and bold leaders, just like a man, but are dismissed as the typical “loud Latinia.” This term stems from the stereotype that Latinas are loud, overbearing and controlling —stereotypes that can limit young Latinas and women of color from expressing themselves for fear of being misrepresented, according to HipLatina.

“Respectability politics teaches us to be quiet, to dress and act like upper middle class Anglo Americans,” said Ethnic Studies Professor Alai Reys-Santos in an interview with HipLatina, who teaches at the University of Oregon. “The danger of respectability politics is to lose our sense of self, one of the largest indicators of success for Latinas and women of color is their connection to their roots, the more empowered they feel culturally, the more they can succeed.”

Although Chávez was known for her quiet heroism and did not speak in public, she was able to accomplish her goals by putting action behind her words and having friends and fellow union workers who supported her.

After her father died, Chávez dropped out of high school and started working in the fields to help support her family. In 1942, the U.S. introduced the Bracero Program, which temporarily imported workers from Mexico to work in agricultural fields and railroads. Throughout the program’s tenure until 1964, it’s estimated over 4.6 million Mexican workers arrived in the United States on labor contracts, according to the Council of Hemispheric Affairs (CHA).

The CHA also states the program was controversial for the unequal power relations under which Mexican migrants were forced to labor and for the abuses they had to endure. Even after the Bracero Program ended, it resulted in heightened migration and low wages for migrant farmworkers and institutionalized the agricultural industry’s reliance on cheap labor. Usually only paying union workers, like Chávez, $5 a week plus food and housing. It was these civil rights violations Chávez would stand up against throughout her life.

The three boys from geometry bullied Angel until they were bored. Not even my teacher spoke out against the act, I guess he thought it was the classic but unjust case of boys being boys. Today, I wish I had spoken out, but I feared being ridiculed and laughed at. A study by the Girls Scout Research Institute shows one-third of surveyed girls said they do not want to be leaders due to fear of making people mad at them, coming across as bossy or not being liked by others.

Chávez’s roles as a business administrator, laborer, activist and caretaker presents her as a role model to young girls and women, like myself, to know that women’s voices are nonnegotiable. The UFW stated she was “quiet and humble but fiercely determined and strong willed, Helen didn’t speak in public, but held deep convictions.”

Chávez was a force to reckon with, especially during a time when women’s role in society was to be a housewife. Her role in the UFW may have been quiet and behind the scenes, but was the driving factor in its accomplishments. While her husband was on the road, as the UFW’s public speaker, Chávez stayed with their children and ran the books, walked the picket line, protested with other farmworkers and also returned to the fields and worked side by side with the laborers she was fighting for.

To top it off, Chávez was arrested in 1978 for picketing a cantaloupe field. Her will to do what was right continued to drive her, in 2008 she was awarded Latina of the Year by the National Latino Officers Association of Los Angeles Chapter for her nonviolent social change for the poor and disenfranchised.

“I want to see justice for the farmworkers,” she told a reporter for The Times in 1976. “I was a farmworker and I know what it is like to work in the fields.”

Almost 10 years later, I still think about that day in geometry class. I should have stood up for what was right —bullying a mentally disabled 15-year-old is not OK— but I didn’t. I cannot help but think how different his life would have been if he had people who looked out for him. Much like Helen, she knew farmworkers would not have been given a fair chance if someone did not speak up.

Helen teaches us to always stand our ground for what we believe is right, especially for marginalized voices. Her life teaches us to be resilient in moments of uncertainty and when the world seems to be against you.

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of individual(s).

Want to read more stories like this? Give us your feedback, here!

Latinitas Magazine is a project of Latinitas, a registered nonprofit. We are funded by readers like you, so please consider donating today. Thank you!