By Martina Vásquez

Alejandra (Aleja) León was my childhood babysitter, but now she is much more than that. Ever since I can remember, I’ve admired her ability to thrive, her commitment, her ambition, and above all, her perseverance: these are all traits of hers that are visible from the outside. But I’ve always known there was something more to her story, an invisible side. Her story has been a cloudy but powerful one in my mind for a long time; in my family, she is talked about with respect and admiration. I wanted to know the details of her life’s journey; I wanted to understand how she has become the person she is.

Alejandra was born on the 8 of May 1995, near the city of Bogotá, Colombia. She spent her childhood living with her family –her parents, an older sister and a younger brother– on the farm where her father worked. The first job her father had was collecting the eggs that a few chickens would lay occasionally; the second was milking the cows that her father’s employers had living in the vast property. This is where Aleja sets her earliest memories: helping her dad gather the eggs, running around on the grass, the sky framed by majestic yet familiar trees. Her cousins lived close by, so she and her siblings spent a great amount of time with them, coming up with new, and giddily entertaining, ways to spend their days.

“I remember one night a eucalyptus tree fell next to my house because it was very old. And it was very tall, too. I didn’t find out, because nothing wakes me up -she laughs a bit, and so do I, and I can’t help but remember all those mornings in which I would wait in front of her door for her to come out,” she said. “Little did I know that most of the time she had been studying all night, and had only gotten to sleep a couple of hours ago. So the next day, when I saw this tree there, filling almost the entire paddock, that was the most fun we’d ever had.”

This grand tree trunk, laying massively on the ground, and its amusing little gumnuts, proved to be the best playground the children could desire. Aleja also remembers a beautiful garden inside the farm, overflowing with flowers and colors, the kind that you keep as a token of childhood happiness.

“Do you have a specific memory from that time, something concrete?”

“Oh, yes, I’m going to tell you my favorite anecdote. The one I tell everybody, you know, when they ask me about the prettiest memory from my childhood, and it’s about my pets,” she said. “I told it to you when you were little, and you were totally captivated by it, though I don’t know if you remember it now. Doesn’t matter, I’ll tell it again.”

When Aleja was around 10-years-old, her family lived close to a couple who had two Labradors: Peluca, a female, and a male called Tomás. Then one day, this couple had to move away to a different city, and they asked Aleja’s father whether they could take in the dogs: a family of three children like theirs, in a rural lifestyle like theirs, could take good care of them. The father was reluctant at first because he didn’t see how he could take in two big dogs and feed them. But he ended up doing it.

Aleja and her siblings took the labradors as their beloved pets. The kids would play with them ceaselessly in the green fields, and when Peluca got thirsty after so much activity, she delighted them by throwing her entire face into her water bowl and emerging soaking wet down to the neck.

Then, Peluca got pregnant. Their father suggested they build a house for all the dogs, because their house, in which the pets currently lived, was no place for who-knows-how-many puppies. So they built it together. Then came the night when Peluca started giving birth, which is a long process for dogs.

“A puppy would come out and then, twenty or thirty minutes later, came the next one. And so on, until they were eleven. Eleven! I remember we were all very invested,” Aleja said. “Every day after school we would go see the puppies. Imagine. Eleven puppies! Then one day, one of them opens their eyes. And she, we didn’t know it was a she yet, she had the biggest eyes. But, because we spent all our time with the dogs, we didn’t help with the chores of the house. So my mom would get home and yell at us, ‘ay, why didn’t you do any of your chores?’ and we went, ‘We don’t care!’ We loved those puppies.”

One day Tomás was sent away. The only explanation the children received was that the dog had bitten a police officer. Peluca, who had hurt her leg some days before and had trouble moving around, became seriously depressed. She barely ate anymore and almost never got up. This is why Aleja’s father decided that she had to be sent away too. That was a sad day in Aleja’s life, the day they came to take Peluca. The dog didn’t have the strength to resist, of course, but she looked imploringly at the children.

“It was this look that said, ‘don’t let them take me, please don’t let them take me.’ And we couldn’t stop crying, a grito herido, and we watched the truck leave with her, getting further and further away, and it broke our heart,” she said. “We kept one of the puppies, but he was different, it all felt different. We even had another dog later on. I have a lot of dog stories, and they’re all just as happy and just as sad.”

Aleja was still ten when her mom started working at a flower shop. Her dad didn’t want her to work at first; he wanted her to stay with the kids, and take care of them. This changed the entire dynamic of the family. Her mom met a man where she worked, and she started going out with him. In their home, even the children could tell something was amiss. Their mother would get home from work, fix herself up a bit, and leave again. This went on for a long time, and Aleja remembers distinctly the deep pain on her father’s face every time he would come back from work only to find that his wife wasn’t home. But rumors in small villages have a way of getting around, and eventually, he heard about the cheating, which only made things worse. The home was no longer a happy place, the parents fought nearly every day and there was always something in the air, something ugly, something hostile.

“I, personally, didn’t believe that my mom was really going out with another man. Between us, as siblings, we would try to decide what we should believe, what side of the story was going to be ours,” she said.

Her mom would lock herself in the bathroom and talk to this other man on the phone, with a very hushed voice, almost whispering, as if they couldn’t hear her. The little brother sat there, though, listening; then, when she came out and he would ask her who she had been talking to, she would say a friend of hers. They, of course, knew she was lying.

Then came the moment when her dad saw the two lovers together, and all the rumors were confirmed. The entire family knew now, there was no going back, the painful days came. The children couldn’t understand why their mom would choose an alcoholic, ill-tempered man instead of their father. The three of them started spending all their time at their cousin’s place, which is why they weren’t there the day their father came home to find that man, his wife’s lover, drunk in his own house.

“I remember that, at that time, my sister was the only one with a cellphone, so my dad called my sister and told her to come home straight away. I don’t know what he told her exactly, but I remember her expression. It was as if the weight of the world had crashed on her,” she said. “She told me, ‘We have to go home, dad called me crying, we have to go home, now.’ I felt a shiver all over my body. Now, this memory I have is very clear, after that nothing was the same again.”

The kids arrived home and found their father crying. He told them he had called the police saying there was a thief in their house. A long time later he would explain that it felt like the safest option because what he really wanted to do at that moment was hurt the man himself. Instead, he called the police and frightened the man, who ran away. The authorities then started looking for him.

Aleja’s mother kept perfectly quiet, as if in a state of shock. For a while now she had been behaving worse and worse, with her family, with her kids, always in a bad mood. They all got closer to her dad because she had become disagreeable in their relationship.

“By then, for example, our paradise garden wasn’t there anymore,” Aleja said. “Obviously it didn’t magically disappear as soon as my mom left. But now, when I remember those days, trying to make some sense of what happened, I realize that the garden was already dying when my mom started behaving differently. We weren’t aware of that at the time, though. All we knew was that she had left us.”

And so a decision was made. Their father sat them all down. There was nothing left to do, he explained.

“He told us, ‘All I can say is that I can’t live without you guys. Do you want to stay with your mom or with me?’ And we were all crying, the three of us wanted to stay with dad,” she said. “My mom didn’t show any kind of sadness or regret. I remember her leaving without a word, going to look for the man. She only came back late at night. A few days later she was moving out.”

Her mom left with the man to live in a different city, and they didn’t see her for a long time. Aleja’s older sister took on the motherly role in the house, doing most of the chores. Except for breakfast: this remained their father’s task all throughout their childhood. It didn’t matter how tired he was or how early he’d had to get up, he never stopped making breakfast for his children.

“Mi papi, he’s the best human being in the world,” Aleja adds, gleefully.

Life, from then on, followed a different set of rules. Above all, Aleja remembers her father’s constant struggle. He had to fulfill every role and every need, make sure his home stayed a happy one, and that his family could keep on living. He woke up before dawn to milk the cows; after that, he went back home to get the children ready for school in time for them to catch the bus; later he would also have to get lunch ready, and often he would go without eating to make sure his children did; at the end of the day, he would find the time to wind down with them in front of a TV show. This was their routine.

In those days, the three siblings felt the need to fill their free time. It was their way to overcome the void left by their mother. They started taking gymnastics classes in the evenings, after school: in Sopó, the little town north of Bogotá, in Colombia, where she lived, sports, arts or other kinds of courses were always available, and most of the time for free. Aleja was eleven then, and she remembers these classes as the first time she had some kind of responsibility, a challenge that she had to put time and effort into.

“This feeling of duty is what sparked in me the desire to do something, to be something. Now I had a purpose, a goal I had to achieve by putting in the effort, all by myself. Nobody was going to do it for me. I liked the feeling of having my own accomplishments,” she said.

Aleja graduated from school in 2011, at a precocious sixteen years of age. That year she worked at a stationery shop.

“Once I was robbed there”, Aleja tells me, laughing once more. “I had to pay half of what had been stolen. It was stupid, really, because I was very naïve. In a village you’re naïve, you trust people. This man comes in, he’s wearing glasses, he wants to recharge his phone through a website. This was a service we provided to people who didn’t have access to the Internet: the customer paid in cash and we recharged the phone. But the place was full at the time, I was distracted, so I recharged his phone before taking the money. When I turned around again he was gone without having paid for what I had given him. I had to work there for four days for free.”

That was her first job. Others would come, but Aleja always knew she wanted to study. Neither of her parents had finished high school, and, as she puts it, she wanted to be better. But how was she supposed to earn a living at the same time? In 2013, an opportunity came up. There was a family looking for babysitters in a nearby residential neighborhood. Aleja had never liked small kids much, but she immediately decided to apply for the job. She was seventeen then: in her official application, she wrote that she was eighteen because she was afraid that they wouldn’t hire her if they thought she was underage.

On her way to the interview, she looked at the houses, the streets, at the gardens; she thought she would love working there.

She was interviewed by “Señora Socorro,” my grandmother, at our house. And that day she met me and my sister.

“I remember that day so clearly! I thought you were beautiful kids, a wonder. I had no idea what was coming to me, really,” she said.

Around that time, Aleja started taking English classes, which she paid for with her salary. But she still wanted to be better. Her mother had been gradually getting closer to them because she had trouble with her new partner: she came to live in her parents’ house in the village every once in a while, and eventually found a job back home and stayed for good. During this process of re-encounter with the mother’s old life, she came by Aleja’s house one day with the news that they were giving scholarships in the village and suggested Aleja apply to the program. To get this scholarship, you had to have had a high score in the ICFES, the Colombian equivalent of the SAT. Aleja did have a high score, higher than expected for someone with her background, so she decided to give it a shot.

The first time she applied, she chose the Universidad de la Sabana, because it was closer to Sopó than other universities which were in Bogotá, and because it offered a path in audiovisual production. Now, this wasn’t what Aleja wanted to study: she had always been interested in architecture. But she wanted to have a stable income, and for many reasons la Sabana was the best way to do that. It was art, anyway, so she would be happy.

“But I didn’t pass. The test was far too hard, and I also had to speak fluent English, which I didn’t,” Aleja said.

The second time she applied, she decided that she didn’t care how far away it was, or if she would have to travel long distances: she would apply for Architecture in the capital, Bogotá. Nobody in her family supported this drive, though, partly because none of them had gone to college. They warned her that her plan was insane, and a terrible idea: she would spend all her money, she would end up broke, and for what? It didn’t make any sense to them. The only people who stood by her side were her sister and her father. But Aleja didn’t care. She wanted to study.

So she applied to Universidad Piloto. The interview went great, and she was accepted, in theory. She was already in her first week when she was refused once more: the scholarship only paid for half the tuition, and her uncle, who had agreed to pay for the other half if she couldn’t, didn’t qualify as her co-debtor.

Despite the two previous failures, Aleja applied a third time to the scholarship, and to the Piloto. This time, she arrived with more confidence, having a certain amount of experience, and knowing how the interview worked. And finally, she got in.

This is where her life as a college student begins. It wasn’t easy: Thursday through Sunday, without fail, she had to take care of us, and she barely had any time for her assignments. Of course, she was pulling all-nighters on a regular basis. Her friends made plans and hung out, and she couldn’t go because she had to work. It got frustrating sometimes for her, but she always kept in mind that it would pay off because it was her dream. After a while, working hard and always demanding more of herself became natural.

Aleja attended college from 2014 to 2019, working on the project she and some college friends had come up with: Taller Paralelo. Here, their objective was to create better spaces and infrastructures for a society, simultaneously using architecture and social studies. And all the while she was taking care of us four days a week. Getting to spend time around us, my family, and this world that was so foreign to her, is what she considers to have been a blessing.

“I came from a place where, for example, the education of children was completely different,” she said. “I really liked this new way of seeing the world, it was more… aware. This was the greatest learning experience I had as a person, morally and ethically. What I liked most was that every one of you was completely different, and that made everything even more harmonious. Politically, too. For example, I was never taught how important it is to vote, what’s a senate, what’s a congress. I loved learning to have this critical position, getting to think for myself. I also started reading around that time. I had always been very disciplined with my schoolwork, of course, but I had never done it on my own initiative. I was always very persevering: if I set my mind to a goal, I won’t stop until I achieve it. And so another experience that marked my life was going to London, which was also thanks to your family.”

Around the same time, a social help program granted their family an apartment: since they wouldn’t be able to keep it if nobody lived in it, and they couldn’t afford to waste that chance, the mom and the three siblings had to go live there, leaving their father back on the farm. This new arrangement proved to be more difficult than expected. Aleja was studying architecture, the sister was taking a cooking course (she aspired to be a professional) and the mom was working during the day and then taking night classes: they barely had any time left for necessary chores like cleaning the house or preparing the meals. That was how they all moved back to the farm where they once had been a family: the parents didn’t regard each other as partners anymore, but the mom took it upon her shoulders to provide for the family’s needs by cooking, cleaning and doing all the other chores. Her presence there assured that everybody was able to keep on their path, and so, in an unexpected turn of events, they all found a brand-new way to be together.

One afternoon, in 2017, my mother asked Aleja whether she would like to study English. She had already taken some classes previously, but Mariana, my mom, suggested she do it more seriously, in Europe, and offered to help. Aleja saw this opportunity as a gift, and when the option came to leave as an au pair for a French family who was going back to France, she was immediately on board. She didn’t enjoy working with them, though: the relationships within the family were hostile, the children were ill-behaved, and Aleja disliked the authority she had been given to punish them. The job became rather an obstacle that she had to surpass before she could get on with her discovery of the world.

The first problem she encountered in France, predictably, was the language.

“I’ll never forget”, Aleja recalls fondly, as I can’t help but chuckle, “that you two told me, if anybody tries to talk to you, you have to say, “Je ne parle pas français”.”

“Je ne parle pas français! It means, “I don’t speak french!””

“Right! Because you guys told me, if they talk to you, you won’t understand, so you need to say this, and I was like ‘alright, got it,’” she said. “I couldn’t buy anything, I couldn’t just walk in anywhere, I couldn’t speak! Once, I ran out of shampoo, so I had to go into a supermarket, bought a couple of things I needed. Then the cashier lady started talking to me, I didn’t understand anything, I couldn’t even get out my sentence, I just paid and left!”

Then Aleja arrived in London. In the mornings she had to clean her employers’ house; then she took her English classes, and then she had to hurry to pick up the kids at school and spend the afternoon taking care of them. Only on the weekends could she have time for herself. What she liked best about her time in London was the people: the sheer diversity of them. She saw Muslim men and women, and confronted all the prejudices that she had been taught while seeing the news coverage of 9/11 as a little girl. She met people from such distant places that she wouldn’t have ever dreamt of in her little village in Sopó. Gradually she became more confident in her words.

She traveled around, not only in England, but also in France, in Spain and in Switzerland. Everywhere she went, delightfully unfamiliar experiences awaited her, sights and sounds that she hadn’t even dared to imagine coming from her small and remote corner of the world. These weeks were breathtaking for her, every second she had the chance to learn something new, and everywhere she looked she could further explore these cultures that were so different from hers. Then the final day came. Her travels were over, and she had to go back to Colombia.

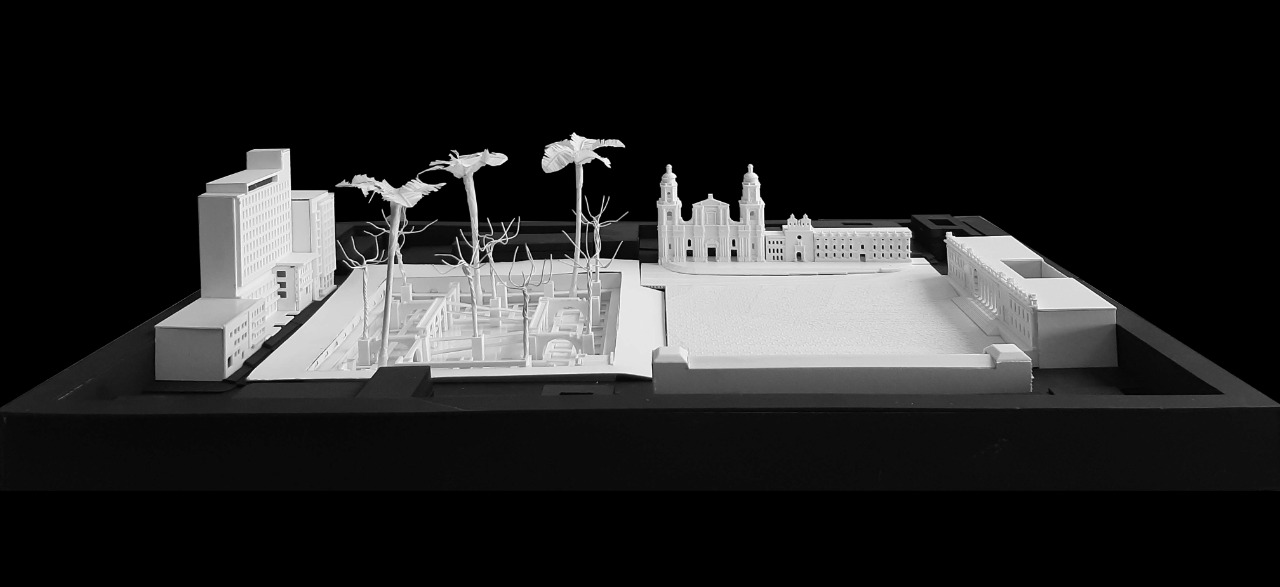

When Colombia went into lockdown because of the pandemic, Aleja, like everybody else, had to stay at home. She couldn’t work anymore, so she plunged straight into architecture. She finished college and graduated with a fascinating thesis. She wrote about fragmentation in the society, and how it translated into fragmentation in the structures built to accommodate said society. Her thesis won the silver medal from the Society of Colombian Architects, a competition they had set in her university. It was an immense distinction. Her prospects were exciting. Eventually, she knew her time with us was coming to an end. It was time for her to focus on her own future.

“To me, it was leaving an important part of me behind,” she said. “I had gotten attached to you all, you felt like my family. So it was hard, but that cycle had to end. I remember I cried a lot, but everybody understood.”

Now, Aleja is working for Martínez Architecture, a respected Bogotá firm, and diving deeper into her English studies, envisioning an opportunity for another scholarship. She is still working hard every day to achieve her goals, her never-ending determination pushing her further and further, the same question always in her mind: “What can I do next?”