On September 16, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, otherwise known as Bad Bunny, released a music video for his song “El Apagón” along with a 20-minute documentary on the disparities and crises happening in his home island of Puerto Rico. The song serves as an homage to the island and speaks of how beautiful and rich with history it is. However, despite the citizen’s efforts, the island itself is not without faults. Case in point, the title “El Apagón” literally translates to “The Blackout”, a common occurrence on the island. In the music video portion, Benito sings, “Damn, another blackout”. This line is paired with a short news piece on the privatization of Puerto Rico’s electrical grid, led by independent journalist and Puerto Rican native, Bianca Graulau.

In 2021 LUMA Energy, a private company from the United States and Canada began operating Puerto Rico’s power grid. While this was originally viewed as a good move, one that would hopefully help the ongoing blackouts that rose in occurrence after Hurricane Maria, it did not. Bianca claims LUMA has made things worse. Following multiple elongated power outages, including a time when a hospital went without power for nearly 20 hours, citizens began protesting in the streets. By featuring this news piece, on top of the title of his song, in this music video, Benito is cosigning citizens’ fears and trying to bring awareness to the at times sketchy business doings of the government. The rest of the documentary piece shows this.

After the actual music video, the video for “El Apagón” transitions seamlessly into a documentary titled “Aqui Vive Gente,” which translates to “People Live Here”. The documentary, also led by Bianca Graulau, aims to highlight the housing displacement crisis that has hit Puerto Rico in recent years and gets to the bottom of why it’s happening. While there are a few stories told throughout the piece, perhaps the most pertinent is that of 68-year-old Maricusa Hernandez, who opens the piece by saying, “They’re displacing Native Puerto Ricans.” And despite not being a native Puerto Rican, she has a point. Maricusa was born in the Dominican Republic but moved to PR in the 90s. She’s lived in the same apartment complex in Santurce for 26 years, and in May was served with a 30-day notice to vacate the premises after the complex changed ownership. Just like that. Out of nowhere. And she’s not the only one.

Puerto Rico native Laura Mía González was also given a 30-day notice to vacate her apartment after the building changed ownership. One business decision and all of a sudden 21 families’ lives were changed. There’s another thing these two cases have in common aside from new ownership; the prices. For 26 years Maricusa paid $600 a month for rent, and the new owners plan on raising this to $2,500 a month once they get new tenants. Similarly, Laura paid $300 monthly, and at the time the documentary was being filmed, her complex had already updated its website to offer short-term apartment rentals for $150 a night. The new owners are essentially trying to get rid of their low-income tenants who have lived in PR for years and rework their buildings into fancy places to stay for the current boom in tourists. Something Laura does not take kindly to, “You can’t come here with a colonizers mentality, thinking that people don’t live here or that the people that did can be discarded with an eviction letter.”

As to why there is a current boom in new tenants and tourism? That’s all due to Act 60. Originally Act 22, now renamed Act 60, the regulation allows for someone to move to PR without paying any capital gain taxes on stock, crypto, or real estate. According to Luxury Collection Real Estate, “The incentives are particularly attractive to US Citizens who move to Puerto Rico because they do not need a residency permit. PR sourced income is exempt from US federal and state income taxes.” The documentary cites that as of June 2022, over 3,000 people in PR are benefiting from this law. This plays into the housing displacement because rather than build up the community, building owners (some from the US), are purchasing apartment complexes, flipping them, kicking the original native tenants out, and pricing them so those tenants could never even afford to stay in that area. As Puerto Rican native Jorge Luis González states, “For 54 years I lived on that corner. Look at it now. A building, a new housing project for the rich. I was born there, and I can’t go there.”

This mentality and practice has disturbing ties to slavery, but for that one needs to understand Puerto Rico’s history. The United States invaded and claimed Puerto Rico as a territory towards the end of the 19th century, and US sugar companies began popping up on the island, “They hired Puerto Ricans as workers and paid them low wages that kept them in poverty,” Bianca explains. “Today, Puerto Rico is still a US possession and these incentives give Americans an advantage and invite them to buy properties in Puerto Rico.” Tourist traps can now hire Puerto Ricans to work under the guise of “more jobs”, but in reality, it seems like history is repeating itself. Kicking out native Puerto Ricans, bringing in well-off Americans to live, and then creating a situation where Puerto Ricans have to now work in the very neighborhoods they used to reside in. And houses aren’t the only thing at risk.

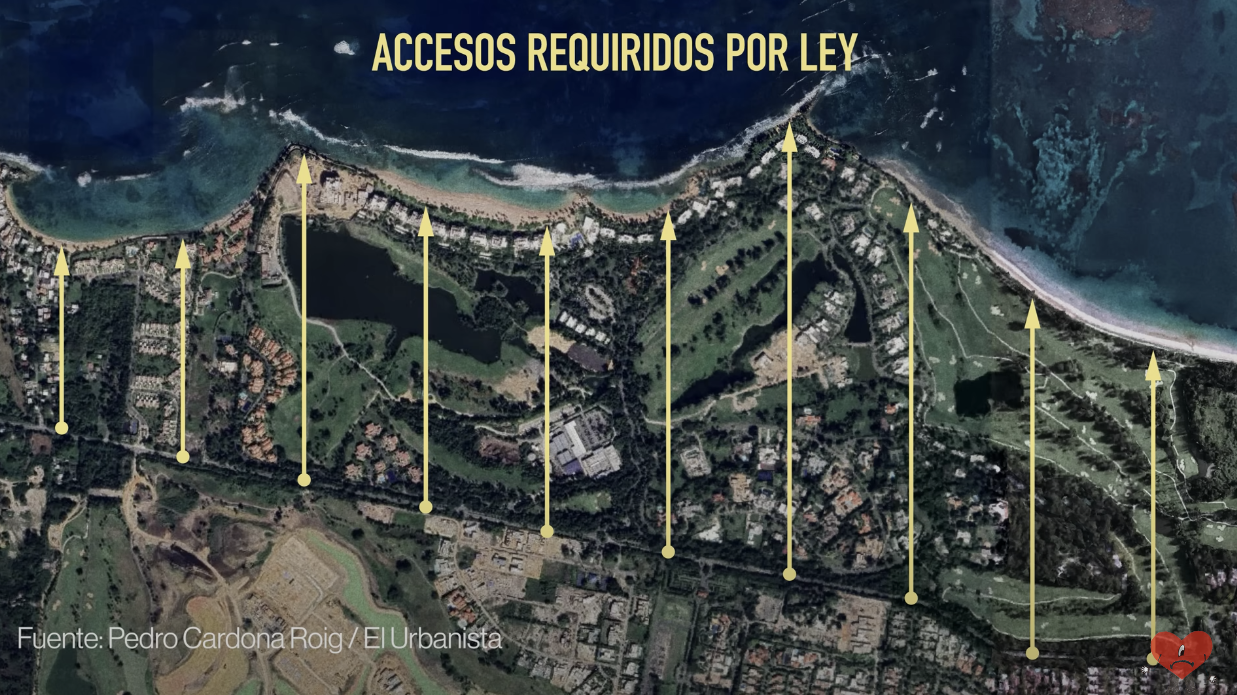

“According to law all beaches are public,” Bianca states, but in recent years these laws are being tested. Dorado is a luxury town on the island, filled with beachfront mansions and fancy hotels. It’s often where celebrities, like Logan Paul, buy houses for themselves, “According to the law, there must be multiple entrances through those private terrains.” But recently, most of the entrances to Dorado Beach have been closed, citing construction as the main reason. Something that’s obviously illegal, the beaches of Puerto Rico are for everyone, and should never be privatized. Currently in order to get to Dorado Beach one must walk over a mile through rocky and slippery terrain, and that’s if the water is low enough. It’s a form of limiting public access, without officially making it private. Therefore, since it’s not technically illegal, it allows businesses to sidestep the law, and give their tenants the feeling of a private beach, without the hassle of one. This sort of law bending is worrying, as the beaches of Puerto Rico should, and have always been, easily accessible and meant for all. As of the time of filming, it seemed like the citizens were on top of this issue, protesting and contacting authorities to enforce the law, but the citizens can only hold out for so long. It’s up to the government and its workers to really enforce and keep Puerto Ricans safe, in every way.

By releasing this documentary and pairing it with “El Apagón”, his love letter to Puerto Rico, Benito is shining a light on these issues. Telling the world not only is he not okay with this, but like the rest of his activism, he will be highlighting these disparities until they are fixed. Unfortunately, as much as Benito is doing, it’s never going to be enough alone. It isn’t up to just the citizens to fight for their rights, at some point the government needs to take accountability and begin protecting Puerto Ricans and their island. Will that happen or will these disparities continue to go unaddressed? Only time will tell.